Knife in the Water (1962)

- Soames Inscker

- May 29, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Jun 7, 2025

Roman Polanski’s Knife in the Water (Nóż w wodzie, 1962) is a taut, minimalist psychological thriller that marks one of the most assured debuts in the history of cinema. Released during the height of the Polish Film School movement, it broke with the dominant trend of war and historical themes to focus instead on contemporary tensions and the theater of interpersonal conflict. Shot on a yacht with only three characters, the film is a masterclass in claustrophobic tension, subtle power plays, and the unsettling volatility of human behavior.

Nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film—the first ever for a Polish film—Knife in the Water signaled the arrival of a major talent and still stands as one of Polanski’s purest, most stripped-down works.

Plot Summary

The film begins with Andrzej (Leon Niemczyk), a confident, middle-aged sports journalist, and his much younger, attractive wife Krystyna (Jolanta Umecka) driving to a lakeside marina for a weekend sailing trip. Along the way, they nearly run over a hitchhiking young man (Zygmunt Malanowicz, whose character is never named). Seemingly on a whim, Andrzej invites the silent, scruffy youth to join them on the yacht.

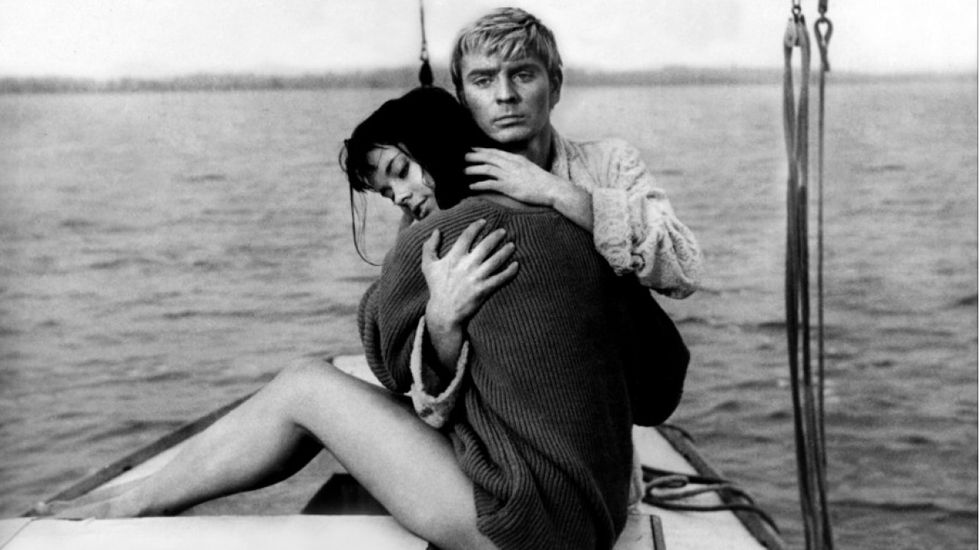

What follows is a slow-burning psychological duel. Andrzej asserts his dominance as the experienced sailor and older man, mocking and belittling the boy. The young hitchhiker, proud and defiant, resists his host’s efforts to humiliate him. Krystyna watches, initially passive, but increasingly drawn to the boy’s quiet independence. Over the course of 24 hours, the atmosphere tightens. Sex, class, masculinity, and violence simmer just below the surface—until the knife of the title plays its part, and nothing can remain the same.

Themes and Analysis

Masculinity and Power

At its core, Knife in the Water is a study in male rivalry. Andrzej, urbane and bourgeois, clearly enjoys wielding authority—over his boat, his wife, and the younger man. He treats the yacht like a microcosmic kingdom, where he is captain and judge. The boy, in contrast, has no material power but possesses the disruptive energy of youth and a quiet, enigmatic confidence.

Their conflict isn’t merely about sailing skills or survival—it’s an existential battle over identity, relevance, and virility. The knife, which the boy carries like a talisman, becomes a symbol of potential violence and the unspoken threat of male challenge.

Class Conflict

The film is steeped in class tension. Andrzej represents postwar Poland’s urban, educated elite—complacent, materialistic, and condescending. The boy, barefoot and nameless, evokes the working class or the marginalized outsider, challenging the patriarchal order of Andrzej’s world. The yacht—a luxury item in 1960s Poland—embodies this divide, a space of privilege into which the boy intrudes and destabilizes.

Sexual Tension and the Female Gaze

Krystyna, at first a background figure in the struggle between the two men, becomes increasingly central. Her quiet frustration with Andrzej’s authoritarianism grows, and her ambiguous attraction to the boy complicates the narrative. She is not simply a passive prize in a male rivalry, but a perceptive observer and, ultimately, the one who reframes the moral compass of the film.

Polanski’s camera treats her not as a sexualized object but as an emotional barometer. Her changing expressions and body language often say more than any dialogue—she is both spectator and participant in the unfolding drama.

Direction and Style

Polanski’s direction is lean, deliberate, and visually acute. With only three characters and a single primary location, he crafts a suspenseful chamber piece, wringing maximum tension from confined spaces and silences. His use of the sailboat—a narrow, unstable platform surrounded by vast water—is ingenious. The lake is open and placid, but the yacht is a prison of egos and gamesmanship.

The cinematography by Jerzy Lipman is crisp and elegant, with striking black-and-white compositions. His camera often glides fluidly around the yacht, capturing the imbalance of power in ever-shifting tableaux. There are lingering shots of rippling water, swaying sails, and wind-ruffled hair that build a poetic sense of unease.

Polanski’s editing is tight, and the pacing—while slow by modern standards—is methodically tense. The sound design is minimalist but effective: creaking wood, lapping waves, and sparse dialogue create an acoustic pressure that adds to the psychological friction.

Notably, the jazz score by Krzysztof Komeda is a standout element. Its cool, improvisational mood contrasts with the rising emotional stakes, lending the film a modern, existential tone akin to French New Wave and American noir.

Performances

Leon Niemczyk is excellent as Andrzej, a man who masks insecurity with arrogance. His patronizing tone and physical assertiveness reveal a man desperate to maintain control.

Zygmunt Malanowicz (dubbed by Polanski himself) conveys a potent mixture of vulnerability and quiet menace. His understated performance suggests a backstory of hardship or disaffection, left tantalizingly ambiguous.

Jolanta Umecka, in her only major role, provides a naturalistic and compelling counterweight to the men’s posturing. Her performance is all the more remarkable for being non-professional—she was reportedly discovered by Polanski at a swimming pool.

Reception and Legacy

When it premiered in 1962, Knife in the Water stood out sharply from the Polish cinematic landscape. Many in Poland’s film establishment were uneasy with its modernity and lack of overt political content, but it received international acclaim. It competed at the Venice Film Festival and received an Oscar nomination, placing Polanski instantly on the global map.

The film influenced a generation of European directors and laid the groundwork for Polanski’s later psychological thrillers such as Repulsion (1965), Cul-de-Sac (1966), and The Tenant (1976). Its minimalist setup and existential tension can be seen in the works of Bergman, Antonioni, and later even in directors like Michael Haneke.

Conclusion

Knife in the Water remains a chilling and elegant psychological drama. It may be minimalist in scope, but its emotional and symbolic depth is vast. With impeccable direction, sharp performances, and a sense of suspense drawn not from plot twists but from the volatility of human nature, Polanski’s debut is a quietly devastating study in control, identity, and the fragility of social masks.

A masterwork of psychological tension and minimalist cinema—an unforgettable exercise in subtle confrontation and submerged violence.