Point Blank (1967)

- Soames Inscker

- May 29, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Jun 7, 2025

Point Blank (1967) is a film of shattered time, splintered identity, and existential revenge. Directed by the visionary John Boorman in his first American production, it takes the skeletal framework of a pulp crime thriller and transforms it into a hypnotic, existential, and almost surrealist neo-noir. Adapted loosely from Donald E. Westlake’s novel The Hunter (written under the pseudonym Richard Stark), the film stars Lee Marvin in one of his most iconic roles—as a man known only as Walker, betrayed, shot, and left for dead, who returns to exact vengeance.

But Point Blank is far more than a standard revenge narrative. Released during a moment of upheaval in both cinema and American society, it blends hard-boiled fatalism with European art-house flourishes. With its nonlinear structure, dissonant sound design, and stark, modernist aesthetic, it both deconstructs and revitalizes the crime genre. It was not a commercial hit upon release, but its critical reputation has only grown over time. Today, it stands as a foundational text in modern noir—a bridge between classic Hollywood and the radical cinema of the 1970s.

Plot Summary

The plot of Point Blank is deceptively simple, even archetypal. During a heist on Alcatraz Island, Walker is double-crossed by his friend Mal Reese and his own wife Lynne, who take the money and leave him for dead. Somehow, Walker survives. He escapes the island and returns to Los Angeles, determined not so much to reclaim his honor as to retrieve the $93,000 he was owed.

But the money is no longer in Reese’s hands—it’s now controlled by a shadowy, corporate-like criminal organization known simply as “The Organization.” One by one, Walker works his way up the chain, confronting various representatives of this faceless enterprise, not to dismantle it, but simply to get his money back.

What follows is a strange odyssey through the alienating corridors of modern capitalism, where revenge seems perpetually delayed, identities blur, and violence erupts with a cold, abrupt finality.

Themes and Analysis

Alienation and Modernism

Point Blank is steeped in alienation—emotional, spatial, and social. From the opening scenes in Alcatraz’s cold, echoing corridors to the sterile, angular interiors of L.A.'s corporate offices, Boorman creates a world where human warmth has been bled out. The film’s Los Angeles is not a city of dreams, but of geometric abstraction: highways, glass towers, airports, and echo chambers.

Walker moves through this landscape like a ghost or automaton, stripped of passion or empathy. His vengeance is not cathartic—it’s robotic. The question lingers: is he truly alive, or is the entire film an extended death dream?

This sense of dissociation is reinforced by Boorman’s radical editing and sound design. Scenes are often elliptical; time is fragmented, with overlapping flashbacks and jarring transitions. Gunshots echo like seismic tremors, footsteps pound like drums. The world is not just hostile—it is unreal.

Deconstruction of the Noir Hero

Walker is a classic noir anti-hero, but in Point Blank he is pushed to the edge of abstraction. Lee Marvin plays him with stoic, glacial intensity—a man stripped down to motive, as if every trace of human complexity has been burned away. He rarely speaks, never jokes, and never shows fear. But the performance is not one-dimensional—it’s haunted. Marvin’s battered face, unreadable gaze, and wounded physicality convey a deep interior pain masked by implacable resolve.

The character's singular obsession with retrieving his $93,000—an oddly precise and relatively modest sum—becomes emblematic of a world where justice and morality have collapsed into commerce. Walker doesn’t want revenge in a traditional sense; he wants restitution, a reckoning in dollars and cents. But the deeper he goes, the more it becomes clear that what he’s chasing may no longer exist—or never existed at all.

Corporate Crime and the Death of the Individual

The central antagonist of Point Blank is not a mob boss or a criminal kingpin, but an organization—an anonymous, bureaucratic entity that absorbs and reconfigures individual criminality into a faceless corporate structure. This makes the film incredibly prescient: the gangster of the 1940s has been replaced by a boardroom executive.

Walker’s quest to reclaim his stolen money leads him up a ladder of increasingly depersonalized figures, each one more removed from the original betrayal, each one passing responsibility upward. By the time he reaches the top, even the ultimate authority figure—Carroll O’Connor’s Brewster—is little more than a functionary, a mouthpiece for an unaccountable system.

In this sense, Point Blank becomes a parable about modern capitalism: vengeance is futile, identity is unstable, and money is a phantom that never truly arrives.

Direction and Style

John Boorman brings a startling visual sophistication to Point Blank. Every shot is meticulously composed, often symmetrical or reflective. Boorman's use of architecture—high-rise offices, sterile apartments, empty freeways—emphasizes emptiness and fragmentation. He frequently uses wide angles, deep focus, and stark lighting to create visual tension without traditional suspense cues.

The film’s color palette is deliberately drained, dominated by cold grays, washed-out pastels, and hard whites. There’s almost no warmth in this world—not emotionally, not visually.

The editing (by Henry Berman) is perhaps the most radical element. Boorman fractures chronology, uses repeated images and sounds to disorient the viewer, and deliberately withholds conventional narrative payoffs. This nonlinearity serves not just as a stylistic flourish, but as a way of expressing Walker’s subjective experience—a fractured consciousness moving through a morally evacuated world.

The soundtrack (by Johnny Mandel) is used sparingly and eerily, avoiding melodrama in favor of a minimal, discordant atmosphere. Much of the film is steeped in silence, broken only by sharp diegetic sounds: a slammed door, a footstep, a gunshot.

Performances

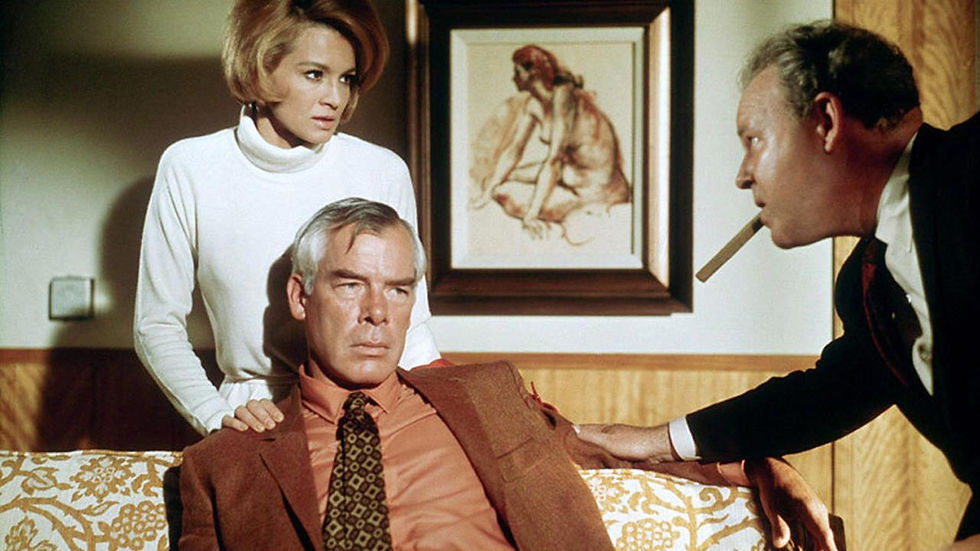

Lee Marvin dominates the film in one of his greatest roles. He imbues Walker with a raw, minimalist power—a man who is less an avenger than a relentless force of nature. Marvin insisted on reshaping the film’s script to match this minimalism, stripping it of exposition and sentimentality. His performance is both emotionally unreadable and psychologically devastating.

Angie Dickinson, as Chris (Lynne’s sister), gives a quietly affecting performance in a difficult role. Her chemistry with Marvin is charged yet fraught; she becomes both a temporary partner and another victim of the vortex Walker creates.

Carroll O’Connor, in a rare villainous role, brings a surprising texture to the role of Brewster, an executive who thinks he’s in control, only to realize too late that Walker cannot be reasoned with.

Keenan Wynn appears as a mysterious, possibly symbolic figure—an observer of the violence, possibly representing law, order, or even death itself. His role is ambiguous and haunting.

Legacy and Influence

Though not a box office hit upon release, Point Blank has since been recognized as one of the defining American films of the late 1960s. Its stylistic innovations helped pave the way for the New Hollywood movement, influencing directors such as Walter Hill (The Driver), Michael Mann (Heat), Nicolas Winding Refn (Drive), and Steven Soderbergh (The Limey, itself a spiritual sequel of sorts).

The film has been remade multiple times, most notably as Payback (1999) with Mel Gibson, but none capture the icy existential terror or the formal rigor of Boorman’s vision. Point Blank stands as a unique artifact—at once genre and anti-genre, pulp and art film, action and meditation.

Conclusion

Point Blank is a masterwork of existential noir—brutal, stylish, and deeply unsettling. More than just a revenge story, it’s a profound meditation on identity, violence, and the dehumanizing machinery of modern life. With Lee Marvin’s towering performance and John Boorman’s bold direction, the film transcends genre conventions to become something altogether stranger and more enduring.

It remains one of the most intelligent and influential crime films ever made—elegant, cryptic, and seething with cold fury.

A stunning deconstruction of the crime thriller—stylishly directed, starkly performed, and psychologically profound. A towering achievement in American neo-noir.