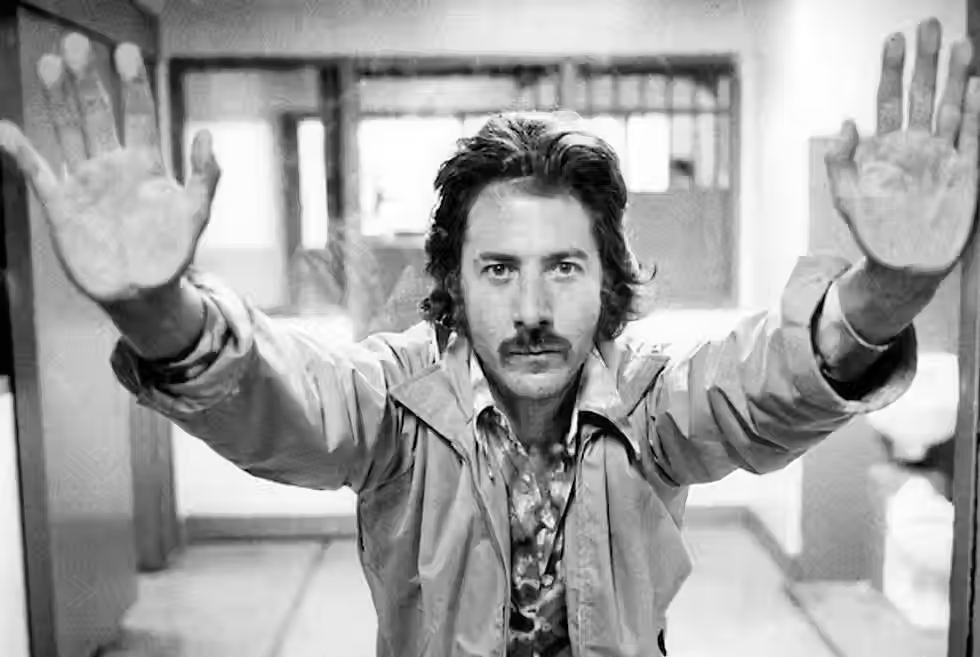

Straight Time (1978)

- Soames Inscker

- Sep 2, 2025

- 4 min read

Released in 1978, Straight Time is a gritty, uncompromising crime drama directed by Ulu Grosbard (with uncredited early direction by Dustin Hoffman). Adapted from Edward Bunker’s semi-autobiographical novel No Beast So Fierce, the film presents a harrowing portrait of recidivism, alienation, and the crushing weight of a society unwilling to forgive. Anchored by a riveting performance from Dustin Hoffman, the film strips away glamour from the crime genre, offering instead a raw, unsentimental exploration of a man trapped in a cycle he cannot escape.

Although less celebrated than other crime dramas of the 1970s, Straight Time remains a haunting, underappreciated gem that resonates with authenticity and bleak realism.

The story follows Max Dembo (Dustin Hoffman), a career criminal who is released on parole after serving six years in prison. Initially determined to go straight, Max takes up residence in a halfway house and secures employment through the state’s system.

However, his parole officer, Earl Frank (M. Emmet Walsh), is petty, sadistic, and unrelenting in his scrutiny. When Max is accused—unfairly—of drug use, Earl humiliates him with a forced urine test and imprisonment in a holding cell. This violation of dignity triggers Max’s disillusionment with the possibility of rehabilitation.

Abandoning his attempts at an honest life, Max reconnects with old associates, including the reckless Willy (Gary Busey) and Jerry (Harry Dean Stanton). He also begins a tentative romance with Jenny Mercer (Theresa Russell), a sympathetic employment agency worker. As Max slides deeper back into crime, his heists grow increasingly desperate and violent, culminating in a botched robbery that leaves his fate uncertain.

Dustin Hoffman gives one of his most nuanced performances. He portrays Max not as a stereotypical gangster but as a man caught between yearning for normalcy and succumbing to ingrained survival instincts. Hoffman balances menace and vulnerability, creating a character both sympathetic and deeply troubling.

M. Emmet Walsh is chilling as Earl Frank, embodying the banality of institutional cruelty. His performance underscores the film’s critique of a parole system that dehumanises rather than rehabilitates.

Harry Dean Stanton lends his usual authenticity as Jerry, the older ex-con whose weary pragmatism contrasts with Max’s volatility.

Gary Busey, fresh from his breakout role in The Buddy Holly Story, delivers a raw, energetic turn as Willy, adding an unpredictable edge.

Theresa Russell, in one of her earliest roles, plays Jenny with quiet compassion. Her relationship with Max represents both hope and inevitability—the tension between redemption and relapse.

Though Grosbard is credited as director, Hoffman initially helmed the project before stepping aside. The film’s fragmented production history does not diminish its cohesion; rather, it enhances its documentary-like realism. Grosbard’s understated style, combined with Owen Roizman’s naturalistic cinematography, roots the film in the grimy streets and backrooms of Los Angeles.

The film avoids stylisation: robberies are clumsy, confrontations are tense and awkward, and violence is quick and ugly. There is no romanticisation of crime—only its drudgery and danger. This realism sets Straight Time apart from flashier crime films of the era.

Recidivism and the Prison System – The film paints a bleak picture of reintegration. Max’s parole officer represents systemic obstacles that trap ex-convicts in cycles of mistrust and punishment.

Max’s inability to connect with the “straight” world highlights the isolation of ex-offenders. Even Jenny’s affection cannot bridge the gulf.

Though Max is released from prison, his “freedom” is conditional, surveilled, and undermined at every step. His slide back into crime is both a choice and an inevitability.

Unlike heist films that emphasise thrill or style, Straight Time exposes the futility of crime. Each robbery brings only short-lived relief, shadowed by paranoia and violence.

The film foregrounds the toll crime and punishment exact on relationships. Willy’s family suffers from his recklessness, Jenny is drawn into a world she cannot comprehend, and Max himself remains fundamentally alone.

When Max is accused of using drugs, Earl forces him into a degrading confrontation that symbolises the systemic cruelty of parole. This is the turning point where Max gives up on legitimate life.

Tense and chaotic, this scene exemplifies the film’s refusal to glamorise crime. The violence is abrupt, the aftermath messy, and the supposed reward fleeting.

Max, cornered, makes a desperate flight that underscores his inability to exist within or outside the law.

Straight Time received strong critical praise but only modest box office returns. Reviewers lauded Hoffman’s performance and the film’s authenticity, though some audiences found its bleakness difficult to engage with.

Over time, the film has gained recognition as an overlooked masterpiece of 1970s cinema. Its raw realism influenced later crime dramas, particularly those focused on character rather than spectacle, such as Heat (1995) and American History X (1998). It also brought renewed attention to Edward Bunker, who later co-wrote Runaway Train (1985) and appeared in Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs (1992).

Straight Time is a bleak but brilliant portrait of a man unable to escape the gravitational pull of his past. With Dustin Hoffman delivering one of his most underappreciated performances, and with Grosbard’s unsparing direction, the film refuses to compromise or sentimentalise.

It is not a film of easy answers or redemptive arcs. Instead, it confronts the audience with uncomfortable truths about freedom, punishment, and the near impossibility of rehabilitation within a broken system. In its refusal to offer comfort, Straight Time achieves a stark authenticity that makes it one of the most powerful crime dramas of the 1970s—an unflinching study of a man for whom freedom is merely another kind of prison.