Tarzan the Ape Man (1932)

- Soames Inscker

- Nov 1, 2025

- 5 min read

The 1932 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer production Tarzan the Ape Man is one of the most iconic adventure films of early Hollywood, a defining moment in the evolution of both the jungle genre and the popular image of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ famed literary creation. Directed by W. S. Van Dyke and starring Johnny Weissmuller and Maureen O’Sullivan, the film not only launched a successful series that would span decades, but also solidified the visual and thematic blueprint for nearly every screen incarnation of Tarzan to follow.

With its mixture of exotic adventure, romance, and spectacle — and its daring portrayal of raw physicality — Tarzan the Ape Man captured the public imagination and helped shape the mythology of one of cinema’s most enduring heroes.

The film begins in British East Africa, where wealthy adventurer James Parker (C. Aubrey Smith) and his partner Harry Holt (Neil Hamilton) are on an expedition in search of the fabled “Elephant’s Graveyard,” a mythical place where elephants go to die and leave behind heaps of ivory. Their quest is interrupted by the unexpected arrival of Parker’s daughter, Jane (Maureen O’Sullivan), who insists on joining the expedition against her father’s wishes.

As the group ventures deeper into the jungle, they encounter both natural and human dangers: treacherous terrain, hostile wildlife, and native tribes wary of outsiders. It is amid this perilous landscape that Jane first encounters Tarzan (Johnny Weissmuller), the mysterious “Ape Man” who rules the jungle with primal authority.

Tarzan’s fascination with Jane — and her growing curiosity and affection for him — form the heart of the film. Their romance, at once innocent and sensual, plays out against the backdrop of the wilderness, where civilisation’s rules fall away. When Jane is abducted by apes and later by tribal warriors, Tarzan’s fierce rescue of her cements his role as both protector and lover, and Jane’s choice to remain with him rather than return to her father becomes the film’s defining emotional moment.

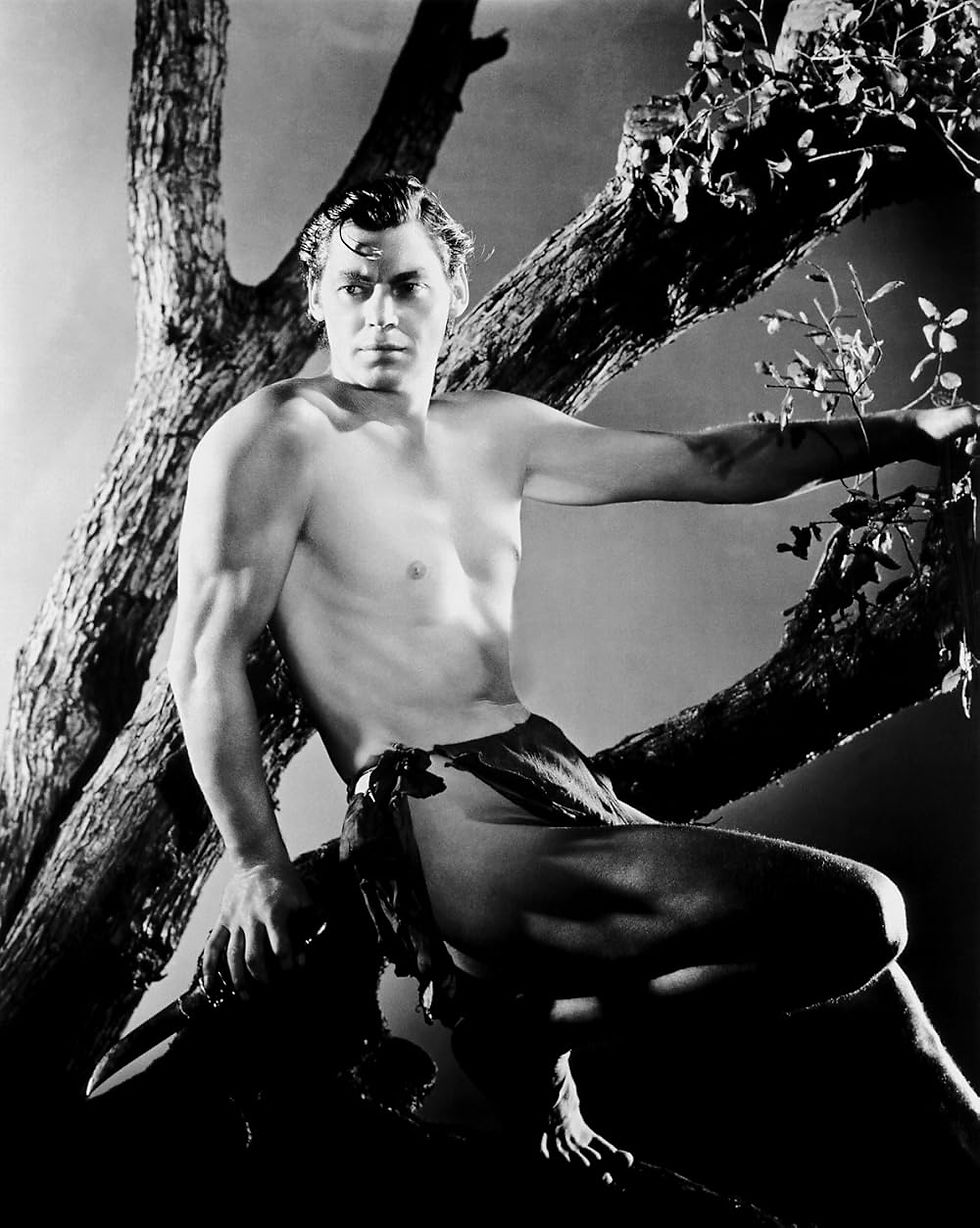

Johnny Weissmuller, a five-time Olympic gold medallist swimmer with no prior acting experience, proved an inspired choice for the role of Tarzan. With his athletic physique, effortless grace, and commanding screen presence, Weissmuller embodied the physical ideal of Burroughs’ jungle hero more completely than any of his predecessors. His interpretation of Tarzan as a noble savage — powerful yet innocent, instinctive yet compassionate — became definitive, influencing every later portrayal.

Weissmuller’s now-legendary Tarzan yell, a blend of recorded yodels and sound effects, became one of the most recognisable sounds in cinema. Though his dialogue is minimal (“Me Tarzan, you Jane” — a line often attributed to the film though not actually spoken), his expressive physicality and natural charisma convey everything necessary.

Maureen O’Sullivan, as Jane, provides a perfect counterbalance. Intelligent, spirited, and increasingly drawn to the freedom of the jungle, she transcends the standard damsel-in-distress archetype. O’Sullivan brings warmth and charm to her performance, and her chemistry with Weissmuller gives the film a surprisingly sensual undercurrent for its time. Their scenes together — playful, romantic, and occasionally daring — are among the most memorable of early 1930s cinema.

C. Aubrey Smith lends gravitas as the dignified but paternal James Parker, while Neil Hamilton’s Harry Holt provides the conventional heroic contrast to Tarzan’s primal allure. The supporting cast of African porters and tribal figures, though portrayed through the colonial lens typical of the era, contribute to the film’s atmosphere of danger and mystery.

Director W. S. Van Dyke, known for his efficiency and flair for adventure (Trader Horn, 1931; San Francisco, 1936), gives Tarzan the Ape Man an impressive sense of scale. The film was shot largely on MGM’s backlot in Culver City, with additional footage taken from Trader Horn and wildlife scenes filmed in Africa and Florida. Through clever editing, these disparate elements blend convincingly to create an exotic and immersive jungle world.

Van Dyke’s direction emphasises movement — swinging vines, churning rivers, charging elephants — creating a rhythm of physical vitality that mirrors Tarzan’s own primal energy. The pacing is brisk, with a steady balance between adventure, romance, and spectacle.

Harold Rosson’s cinematography enhances the film’s atmosphere, capturing the jungle’s lush density and its dangerous allure. The interplay of light and shadow in the jungle sequences evokes both mystery and eroticism, particularly in scenes between Tarzan and Jane, where nature itself seems to mirror their growing attraction.

At its core, Tarzan the Ape Man is a study of civilisation versus nature, of order confronting instinct. Jane’s journey into the jungle becomes a symbolic shedding of social restraint — a movement from the rigid propriety of Victorian civilisation to the liberating chaos of the natural world. Her decision to remain with Tarzan at the end suggests both a romantic surrender and a deeper philosophical one: that there is a purity in nature that civilisation has lost.

The film’s portrayal of Tarzan as noble yet uncivilised reflects the contemporary fascination with primitivism — the idea that man, stripped of the trappings of society, might rediscover his essential humanity. Yet it also carries the problematic colonial attitudes of its time. The depiction of African tribes, while typical of 1930s Hollywood, is steeped in stereotypes and reflects the paternalistic worldview of Western adventure cinema.

Nevertheless, the film’s emotional core — the love story between Tarzan and Jane — transcends its dated attitudes. Their relationship is portrayed as both tender and elemental, free from the hypocrisies of polite society. In its own way, it anticipates the sensual freedom and rebellion against convention that would come to define later cinematic romances.

The film’s sound design, particularly Tarzan’s yell, became one of its most famous contributions to pop culture. The musical score, while sparse, effectively underscores the film’s atmosphere of wonder and danger. Jungle noises — the cries of animals, the rustle of foliage, the distant drums — provide a constant aural backdrop, immersing the audience in a world that feels untamed and alive.

Tarzan the Ape Man was a tremendous success upon its release, both critically and commercially, establishing Johnny Weissmuller and Maureen O’Sullivan as major stars. The film’s popularity led to a long-running MGM series, with Weissmuller and O’Sullivan reprising their roles in numerous sequels, including Tarzan and His Mate (1934), Tarzan Escapes (1936), and Tarzan Finds a Son! (1939).

Its influence on cinema and popular culture is profound. The film codified many of the visual and thematic elements now synonymous with Tarzan — the vine-swinging, the yell, the loincloth, and the depiction of the jungle as both paradise and peril. It also paved the way for later adventure films and serials, from King Solomon’s Mines to Indiana Jones, establishing the jungle as a cinematic space of both danger and self-discovery.

Though modern audiences may find aspects of its racial and cultural depictions uncomfortable, Tarzan the Ape Man remains a landmark in film history, both for its technical achievements and its role in shaping early Hollywood mythology.

Tarzan the Ape Man (1932) endures as one of the defining adventure films of the early sound era — a heady blend of romance, spectacle, and primal fantasy. Johnny Weissmuller’s debut as the jungle hero gave the world its definitive Tarzan, while Maureen O’Sullivan’s Jane provided both intelligence and emotional depth. Under W. S. Van Dyke’s vigorous direction, the film captured something elemental about human nature’s dual longing — for adventure and for belonging.

Though viewed today through a more critical lens, its historical significance and cinematic energy are undeniable. More than ninety years after its release, Tarzan the Ape Man continues to swing confidently through the annals of film history — a thrilling relic of Hollywood’s golden age, and the beginning of one of cinema’s most enduring legends.