Gremlins (1984)

- Soames Inscker

- May 5, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Jun 8, 2025

Overview

Gremlins is one of the most iconic and genre-bending films of the 1980s, blending horror, comedy, fantasy, and satire in a unique package that feels both nostalgic and subversive. Directed by Joe Dante and produced by Steven Spielberg, this holiday-set creature feature explores small-town Americana under siege by mischievous monsters born of consumer irresponsibility and magical folklore.

Upon its release in 1984, Gremlins was both a critical and commercial success, earning praise for its innovative tone and visual inventiveness. It also stirred controversy for its surprisingly intense content, contributing to the creation of the PG-13 rating in the United States.

Underneath its B-movie thrills and anarchic slapstick is a clever, sometimes biting commentary on capitalism, tradition, and suburban conformity, making Gremlins a rare film that manages to be entertaining, unsettling, and intellectually engaging all at once.

Plot Summary

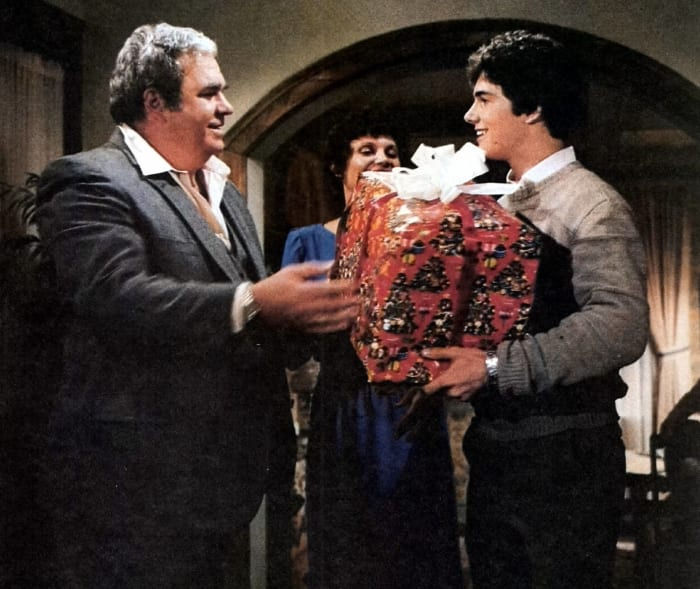

The story begins with Randall Peltzer (Hoyt Axton), an eccentric inventor, who discovers a mysterious, furry creature called a Mogwai in a Chinatown curio shop. Despite the shopkeeper's warnings, he buys the creature—named Gizmo—as a Christmas gift for his son Billy (Zach Galligan). The Mogwai comes with three simple but ominous rules:

Do not expose it to bright light.

Do not get it wet.

Never, ever, feed it after midnight.

Inevitably, all three rules are broken. When Gizmo gets wet, he spawns new Mogwai, who are far more aggressive. These spawnlings trick Billy into feeding them after midnight, transforming them into destructive, reptilian Gremlins.

The town of Kingston Falls quickly descends into chaos as the Gremlins terrorize citizens, sabotage infrastructure, and turn the cosy holiday atmosphere into a nightmarish carnival of destruction. Billy and his love interest Kate (Phoebe Cates) must rally to stop the menace—while Gizmo, loyal and pure, becomes a reluctant hero.

Themes and Interpretation

1. Consumerism and Suburbia

Released during the height of Reagan-era consumerism, Gremlins is both a love letter to and a satire of American middle-class life. The small town is a Norman Rockwell painting come to life—complete with tree-lighting ceremonies and perfect lawns—until the Gremlins expose its darker undercurrents.

The creatures themselves are a literal product of broken rules and unchecked desire, born out of greed, negligence, and the pursuit of novelty. They invade the very symbols of American comfort: the kitchen, the movie theatre, the shopping mall.

2. The Uncanny and the Monstrous

Gizmo represents the innocence of fantasy—cute, loyal, magical. But once corrupted, Mogwai transform into manifestations of chaos and id—self-indulgent, violent, mocking humanity itself. The film cleverly blurs the line between comedy and horror, making the Gremlins both hilarious and genuinely disturbing.

They’re not just monsters—they’re mirror images of us at our worst: binge-eating, vandalizing, watching violent films, drinking excessively.

3. Deconstructing the Holiday Spirit

Set at Christmas, Gremlins plays like an anti-Christmas movie. While the aesthetic screams holiday warmth, the content is often bleak or cynical. Kate's famous monologue about her father's death in a chimney is a dark parody of holiday storytelling, emphasizing how trauma often lurks beneath the surface of seasonal cheer.

Direction and Visual Style

Joe Dante brings a tone of cartoonish anarchy to the film, heavily influenced by Looney Tunes and B-movie horror. The result is a strange tonal alchemy—one moment adorable, the next grotesque. Dante keeps the pacing brisk, balancing suspense and slapstick without losing narrative coherence.

The film also benefits from fantastic practical effects. The Gremlins—designed by special effects wizard Chris Walas—are animatronic marvels. They’re expressive, tactile, and believable even by today’s standards. Gizmo, in particular, remains one of the most charming creature creations in cinema history.

The set design reinforces the film’s themes—Kingston Falls, with its snow-covered streets and cosy shops, is visually reminiscent of It’s a Wonderful Life, but the Gremlins’ presence turns it into a kind of warped, nightmarish Disneyland.

Screenplay and Dialogue

Written by Chris Columbus, who would go on to direct Home Alone and Harry Potter, the script is deceptively simple but rich in subtext. The rules of the Mogwai are a stroke of genius—so specific, yet so vague that you know they’ll be broken.

Dialogue is punchy, filled with 1980s charm and genre call backs. While the film isn't overly talky, it delivers memorable moments—whether it's the shopkeeper's ominous wisdom, Stripe's sneering cackles, or Kate’s haunting backstory.

Performances

Zach Galligan (Billy Peltzer): Galligan brings an earnest, boy-next-door likability to the protagonist. He’s not overly heroic, which makes him relatable.

Phoebe Cates (Kate): Cates adds depth to what could have been a stereotypical love interest. Her deadpan delivery of the now-infamous chimney story is both tragic and darkly comic.

Hoyt Axton (Randall Peltzer): As the bumbling inventor and narrator, Axton injects gentle satire into the film’s portrayal of innovation-gone-wrong.

Corey Feldman: As the mischievous neighbour kid, Feldman adds early comic relief, long before his more prominent roles in The Goonies or Stand by Me.

Keye Luke (as the mysterious shopkeeper Mr. Wing): He brings gravitas and a folkloric wisdom that gives the film its mystical edge.

Of course, Gizmo and Stripe steal the show without ever uttering traditional dialogue. Their expressions, sounds, and body language (voiced by Howie Mandel and Frank Welker, respectively) make them enduring characters in the annals of movie monsters.

Music and Sound Design

Composer Jerry Goldsmith provides a score that shifts masterfully between whimsical, eerie, and frenetic. The main Gremlins theme is a playful yet malevolent carnival tune that captures the spirit of the creatures perfectly. The music elevates every scene, from quiet holiday moments to full-blown pandemonium.

Sound design is also crucial—cackles, purrs, growls, and mechanical mayhem fill the soundscape, immersing viewers in the chaos.

Reception and Legacy

Upon release, Gremlins was a box-office hit, earning over $150 million worldwide on a budget of around $11 million. However, it sparked controversy for being marketed as family-friendly despite its violence and horror elements, helping prompt the MPAA to create the PG-13 rating.

Over time, Gremlins has become a cult classic, influencing decades of horror-comedies (like Critters, Tremors, Slither), and even animated shows and video games. It’s regularly cited among the best Christmas movies and best creature features, occupying a rare space in both lists.

A sequel, Gremlins 2: The New Batch (1990), leaned even more heavily into satire and self-parody, becoming a cult favourite in its own right.

Criticisms

Tonal Whiplash: The film jumps rapidly between goofy comedy and genuine horror, which can feel jarring to some viewers—especially parents expecting a child-friendly romp.

Thin Character Arcs: While fun and well-acted, the characters serve more as archetypes than fully developed individuals.

Simplified Moralism: The “three rules” concept is never fully explained (what does “after midnight” mean, anyway?), leaving some thematic ambiguity unaddressed.

Conclusion

Gremlins is a mischievous masterwork of genre cinema—a movie that upends expectations and blends charm with chaos. Joe Dante's film is packed with subtext, satire, and unforgettable imagery, all while remaining a rollicking, accessible thrill ride.

It’s a parable disguised as popcorn entertainment, with monsters that amuse and disturb in equal measure. Whether watched as a holiday tradition, a nostalgia trip, or a clever critique of 1980s excess, Gremlins remains one of the most inventive and enduring films of its era.

A sharp, funny, and fantastically weird Christmas creature feature with heart, teeth, and a wicked grin.